- Last Updated: March 29, 2019 Clothing designers use a process called “draping” to create bespoke dresses from their sketches. They drape a muslin fabric over a dress form and pin it into place. Once the draping is completed, you can transfer the measurements to paper for a pattern or repeat the process with your finished dress fabric.

- Draping is very important skill for fashion designers. It is the process of positioning and pinning fabric on a dress form to develop the structure of a garment design. After draping, the fabric is removed from the dress form and traced on paper to create the pattern for the garment. Draping can be approached in 2 ways mainly 1.

IMPORTANCE OF DRAPING Draping is considered an important skill for up-and-coming designers because it teaches the art of putting a piece of clothing together on a dress form before creating a sketch. The art of draping teaches a designer how darts and seams give a garment shape and a perfect fit. Knowing about darts and seams helps a designer. Sketch your garment. Submit a drawing of the garment you want to create. Include details such as color and type of fabric. Bonus points if you include sketches from different viewpoints: front, back, and side. Prepare your dress form. Use adhesive tape to trace an outline of your design on to the dress form. This process is similar to. You kind of want to be fluid, because draping is fluid. Then, this dress that I'm drawing here in particular drapes from the hip, a corseted wrap dress. I just carry my lines directionally, because you want to do it in the direction in which you want the draping to happen. On this particular dress the draping comes from both directions.

- To reduce the amount of cowl in the front neck.

- To redirect the skirt drape toward the hip area and not the hem.

- To square off the waterfall detail and move it further down the dress to enable a better fit around the seat and thighs.

- To pinch in and alter the back collar to sit better.

- To reshape the cap sleeve to fit the shoulder better.

- Extend the shoulder line for a cap sleeve of 8cm, then curve to fit the shoulder. The drop is approx. 4cm.

- Draw in the new neckline from a mid shoulder point, to a high 'V' neckline.

- Add a 3cm rectangle as the basis for a built-up neckline.

- Curve the right side panel seams out of the new cap sleeve armhole, around the bust and toward the left side low waist.

- For the left side panel seam curve from the same point in the armhole toward the left side low waist position.

- Transfer the left waist dart onto the new panel line.

- Extend the left side panel line through to the hem.

- Place your waterfall feature on this line starting near the top of the thigh.

- Mark in the dashed lines for the skirt drape to be included.

- Taper the side seams of the skirt.

- Build similar cap sleeve, panel lines and built-up neckline for the back dress.

- Taper the back dress below the back waist dart to allow for a panel/dart in the back dress.

- Shape the back waist by min. 1cm through to the hip and across back levels.

- For the front upper bodice transfer all the bust darting into a front neck cowl with a deep turnback facing.

- Cut open the skirt section of the dress and add 8cm for each tuck. Lift the line for the waterfall drape to a 90 degree angle and curve back to the hem.

- Copy the left side panel shape and add the same waterfall drape to the panel seam.

- Taper the back dress by folding out 4-5cm under the back waist dart. This will open up the panel toward the armhole and allow for the addition of seam allowances and cutting.

- Add a deep facing to the back built-up neckline.

Home >Directory of Drawing Lessons > Drawing Objects & Things> Drawing Drapery and Folds > How to Draw Draped Figures & Drapes

Draping Dress Form

Learn how to draw folds, wrinkles, and the draping of clothing, fabrics and draped figures with the following drawing tutorial.

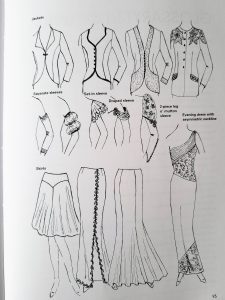

The Text Above is Actually Made up of Images, so if You Need to Copy Text, Please Do So Below. Thank you. DRAPERY AND HINTS ON COSTUME DESIGNINGInto detail of a composition with figures, either 1 in modern dress or costume, does individual impress show more than in the technical rendering of drapery. Although the artist may carefully fix the drapery when sketching from a costumed figure, so that he can easily and faithfully copy it, there will always be some of his own mentality in the interpretation. Drapery will not stay fixed, it cannot be copied mechanically. How it is drawn and how much of the detail is put in depend on the artistic talent of the draftsman. In the case of the costumed model, the slightest move will change the disposition of the folds, and it is impossible, when the model resumes a pose after a rest, to arrange things as they were before. Again, if a lay figure is used, gravity will slowly modify the forms of the folds. In drawing drapery, memory and selection are brought into play. Just how much memory helps depends on the degree to which that faculty has been developed, and selection is shown by the way the artist's personality asserts itself in choosing those folds, creases, and furrows that make a successful piece of work. The illustrations in this chapter from the engravings by Diirer and Schongauer, and of the statuettes of the mourning monks shown in simple outlines, are presented to bring out a certain characteristic feature of drapery. This is that folds and furrows, considered as simple outlines or areas of tones, exhibit somewhat triangular or at times trapeziform contours'. Again, lines defining drapery forms are never parallel. Even in a curtain with long horizontal ridges and furrows, there will be a tendency to the triangular, in that the defining lines converge to points of attachment and slightly flare out at the lower border of the curtain. A semblance to the triangular seems to be the most frequent form that folds. take in a simply draped piece of material. This peculiarity is well exemplified when some stuff is fastened and loosely hung between pins; the material will fall into a series of festoons that are outlined by the radiations that start from the fastening pins. Roughly described, these festoons can be said to be formed of a pair of long triangles each. In this illustration gravity pulls the material downward, and the two pins acting as resisting forces make, as it were, three forces at work. This produces in some thin fabrics very sharply defined triangular forms, but in thicker or very heavy textiles a fourth force is brought into play, i. e., the stiffness or special nature of the threads and filaments of which the stuff is woven, which has a marked effect in modifying the triangular character of the drapery folds. It is important that the artist remember this triangular feature of drapery; not with the idea of getting a monotonous repetition of it in every study; but to help in seeing and understanding what he sees. Compare the manifold forms occurring in the different kinds of materials that come under your eyes when studying from draped figures. In some goods of a pliable texture, the outlines and angles will be softened and the three-sided forms be nearly lost; whereas a stiff fibre in a coarse material causes a number of unexpected breaks at places, especially at the angles. Laces and some delicate material cannot be successfully depicted by lines, particularly straight ones. So it seems that here there is an exception to the rule. On looking closely, however, it can be seen that the flounces formed by such stuffs are defined by what can be called curvilinear triangles. Perhaps an example of what you consider a poorly worked-out bit of drapery comes under your observation. There is something about it that does not satisfy your artistic expectations. Very likely you are right. A critical examination will perhaps show that it is characterized by an entire absence of this triangular or trapezium-like feature of folds, creases, and wrinkles. Of course, one must count upon some exceptions to this, as well as other, rules. For instance, in some subject for a character sketch, say, a needy person who has worn the same garments so long that they have become part of him. The material as it envelops his form shows very little of the triangular in wrinkles and folds. Now place side by side, for the sake of comparison, a fashionably dressed person and a man in rags and tatters. Note how the elegant attire of the one has rigid creases, precise and formal lines and curves. No provision is made for human elbows or knee-joints in the tube-like sleeves and trousers, and when the limbs are bent the occurring creases break in a stiff and mechanical way. In the other subject the apparel has long since lost its distinctly textile character and has gradually moulded itself to the figure that it covers, and in sketching from him the human form must be considered. But not so in the case of the other subject. Here the whole object of the tailor apparently has been to conceal the outline of the human body, so that sketching any one clothed with fresh examples of the sartorial art requires just the knack, one might say, of drawing drapery. well, This accomplishment is attained by merely paying attention to the triangular tendency in drapery forms. This peculiarity, of which we have been speaking, holds with respect to statuary as well as pictorial delineation. A visit to a collection of plastic art will show that we can get hints on the treatment of drapery from the sculptor's works. And from his way of working, too, we can learn what will aid us in drawing the attire of the clothed figure. You need to sketch, for instance, a bit of drapery in action—a floating mantle, something fluttering in the wind, or part of a dress of a figure in movement. To help in getting these effects use a piece of coarsely woven cloth moistened with a thin mixture of plaster of Paris and water. This you fasten to a board and arrange, while still moist, in accordance with the desired effect. Then when it has dried and the plaster has set you can sketch it with ease. Another way, easier and likely to answer every purpose, is to take heavy but soft textured wrapping paper, moisten it and push into such similitude of moving drapery as you can, and then leave it to dry. It will be necessary to tack it in places, either to a board or on the wall. In a model of this sort, it is best, rather than copy the creases of the paper exactly, to take only hints and suggestions and such lines and effects as are best adapted for the drawing. The details from engravings by Darer shown a thin mixture of plaster of Paris and water. For the more serious study of drapery, sculptors sometimes rough out a small figure in clay which they clothe with some thin material (cheese-cloth is good), moistened with clay water or dipped in a thin solution of plaster. The material while still moist is manipulated or pushed around until it is disposed to suit the plastic requirements. As a matter of course, more or less skill is needed in carrying out these little expedients just mentioned. A feeling for the decorative is required in fixing folds and creases in easy flowing lines and to make them fall in harmoniously proportioned masses. For the artist with an originality of conception or the faculty of giving his work a whimsical turn there is no department of practical art that affords more scope for the exercise of his talents than that of designing stage or fancy dress costumes. Especially is this so in the planning of the multicolored apparel for spectacular entertainments. Sketches for the dressing of a classical play or a tragedy of some stated historical period require serious and diligent research for correct details of the costumes of the respective period. For this kind of work the artist, besides consulting the recognized authoritative books on costume, such as Racinet, Hottenroth, Kretschmer, and Hope's 'Costumes of the Ancients,' can find a great deal of material by going over old engravings and in studying the details of early paintings. In designing classical costumes or fancy dress in a quasi-classical manner, nothing could be better than going direct to the Greek painted vases and Tanagra figurines in art museums. A study of the vase pairiting will repay you, not only on account of the knowledge which you will acquire in regard to the ancient dress, but also in teaching you to Costume Suggestions from appreciate the straightforwardness of the line work in these pictures. The Tanagra figurines make clear exactly how the large mantles enveloped the figure. In designing fancy dress of a spectacular or an extravagant order, the artist's imagination is allowed full play. Besides getting his details from any period or style he pleases, he can find motives in peculiar natural forms—shells, flowers, and leaves, for example. And, as for color combinations, what more inspiring hints could be asked than those contained in the coloration of the plant and animal life of the sea, and in feathers, minerals, and crystals? The sameness and want of variety of the figure poses in costume designers' sketches is a conventionality which cannot very well be helped, as the figures must be drawn in such a way as best shows the merits and details of their designs. Costume sketches are usually made in watercolor—either transparent, body-color, or a combination of the two. In addition there are a few little devices that can be employed in producing striking and sparkling sketches. They are as follows: Thick white paint (Albanine is good) for lace and fluffy effects. Put it on in relief in rows of dots, or spatter it. Gum-water, or, as it is sometimes called, watercolor varnish. Paint it in to brighten parts of the design and to add richness to materials like velvet and silk. Iridescent flitter, a powder of minute pieces of colored metallic foil. Paint gum-water where you want the play of metallic colors, and then dust the flitter over the place. Good to show brocade and the glitter of colored spangles. Frosting, or minute particles of mica. Also to be powdered over gum-water, for silver tinsel and spangles. Bronze paints of gold and silver to indicate jewelry. It should be put on thick, somewhat in relief. The showiness of bijouterie can be emphasized by painting the bronze on a raised or embossed foundation. The raised gilding as done by illuminators is worked out by painting the letters in a thick composition of pipe clay and plaster with gum-water. This foundation when dry is sized and covered with gold-leaf. One can imitate this effect by making the raised foundation with a thick white paint to which a little gum-water has been added, then covering with an ordinary bronze paint. Gold or silver powders can also be made to adhere with gum-water. |

Draping Dress Sketch Pattern

Privacy Policy ..... Contact Us